Making Wood Bucks and Learning about Aluminum

6/03/01 Making Wood Bucks and Leaning about Aluminum

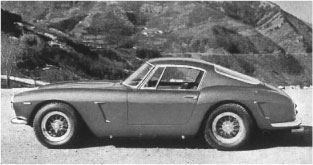

Living in NYC has its advantages and disadvantages, but when it comes to working on wood, it certainly has it’s problems. I live in an apartment, and if I wanted to cut some wood, you can imagine how sawdust can get everywhere! Setting up shop on the sidewalk is not really an option. Luckily, I have a nice area at work I can do my wood cutting. Since it’s a working theater, we have all the usual carpenter’s power tools, and the guys are usually pretty tolerant of my projects as long as I stay out of their way and clean up after myself.

We had to work this weekend, so on my lunch breaks, I set to work making the wood bucks for the heat shields. These bucks will make the bends on the edges more accurate, and may even help keep the aluminum from cracking. It took two extended lunch breaks to finish the bucks, but I think it was worth missing lunch!

The bucks are made out of 3/4 inch plywood, and will sandwich the aluminum. I will then hammer the extended edges much like I did with the prototypes, but this time they’ll be even better!

As I carried these bucks home, I walked by the Empire State Building with them tucked under my arm when it occurred to me how strange it must be to live in this city trying to restore an old Ferrari. Out of the millions of people that live here, how many could be doing the same thing?

Since my last post on the frustrations on working with aluminum, I’ve gotten a lot of good advice on what kind of aluminum to buy. I want to thank everybody who responded, and share with you what I learned.

Yes, there are three types of metal shears. red handled, green handled, and yellow handled. Yellow is for making straight, and slightly curved cuts. Red and green is for making tighter left and right hand turns. The shape of the blades allow for an undistorted cut on different sides depending which shears you use. As with any tool, practice, and patience, and more practice helps make good clean cuts. I’m still practicing!

I believe the cracking I experienced was from “work hardening” that is a process where aluminum, and other metals, actually get harder the more you bend it. The simplest demonstration is when a wire is bent back and forth until it eventually breaks at the bend. Aluminum is often mixed with other metals to give it strength, but this often makes it more brittle. Although pure aluminum will be more flexible, it has its limits before it too will crack. Starting with the purest aluminum will give me the best chance at creating these heat shields just like the factory did. Knowing the classification of aluminum alloys will help when purchasing the right stuff. A good web site sent in by Deane is:

http://www.tpub.com/air/1-24.htm

I learned that 1xxx aluminum is probably what I need to buy, but other alloys may also work sacrificing a little in workability, but I don’t want to find out four hours later after working the shields into shape that it’s the wrong stuff AGAIN!

Mike also sent in a detailed description of his experience fabricating heat shields:

Make sure the aluminum you have is dead soft, not 6061 or any of the stiffer alloys. You should be able to easily bend the sheet with your fingers, and it should not spring back at all – it will almost feel like the lead foil that used to be used to cover wine bottle corks. If you have the stiffer alloy, it takes very little work-hardening to make it crack. For cutting the parts out, there are left and right cutting aviation snips – these are available at Sears and are designed to facilitate cutting either left or right circles. By removing the excess material as François suggested, then using whichever snip gives you better access, you should be able to make very clean cuts even on tight inside corners. The soft aluminum sheet cuts beautifully with these – it’s even kind of fun to watch the part take shape. When folding over the curved sections, support the overlapping edge at all times as you fold it over. You can use a block of wood, or an appropriate auto body buck (I think that is the right term). Use a ball peen or round-head auto body hammer and work slowly – the idea is to stretch the metal by extruding it between the hammer and the buck, but this only happens over a small area for each hit of the hammer. Again, the alloys are no good for this as they work harden and crack instead of stretching. One of the 308 heat shields had a 3″ circular depression right in the middle with a central hole for access to one of the exhaust sniffer ports on the header – this is similar to the depressions on the edges of your shields. To form this on my shields, I made a male and female “mold” out of 1″ particle board, and created the dimple by first gently hammering the heat shield (assembled, with both layers of aluminum and the asbestos cloth) into the female form to stretch the metal (probably about 50% of the total depression), then placing the male form into the depression and hammering that down to complete the forming. I cut the hole after the forming was done, to reduce the chance of splitting the edges during forming. It came out indistinguishable from the original (except for the lack of 20 years of wear and tear). For your edge forming, I’d recommend creating a similar form, and devising a way to securely clamp the heat shield against the female form when working with it. Building these heat shields was my first real experience at metal-forming. They turned out quite nice, and have held up nicely through two years of driving. Anyway, I hope these tips help. Good luck with the job – I really enjoy following your restoration on the web page. Mike Kelly ’79 308 GTS Euro

I also learned that heating the aluminum occasionally to a specific temperature in between the hammering process will also help keep it from work hardening. This process is called annealing, and helps recrystalize the aluminum structure that have been broken down from hammering making it soft again. The temperature (well below melting point) and duration varies, and is too complicated for me to learn, but practice with a torch, and experience will certainly help! Since I’m no metallurgist, and don’t have years of experience working with metal, I’m hoping I won’t have to go to this step!

Stay tuned to the saga of aluminum bending!

Previous Restoration Day

Next Restoration Day

Ferrari Home Page

www.tomyang.net